Dear Storyteller,

When you were a child, did anyone ever scold you for “telling stories”? As though stories were synonymous with lies?

We’re all telling stories. All the time. We’re telling stories to ourselves, about ourselves. (Cue Brené Brown’s work on vulnerability and authentic connection.) We’re also telling them to others. And usually those stories we tell include people, places, and things across specific points in time. We use layers of memory and imagination, our senses and our emotions, to make meaning and “get to the bottom” of an experience. Or, in other words, to dig deep for what we know to be true.

In an earlier note, I talked about the stories we return to, the histories that shape our identities and remind us of who we are. Almost like my own personal fairytale, one of the stories I find myself retelling is about a retreat I took to Northern Ireland, and I want to share it with you. (You can skip down to the bottom to read it, or listen to me reading it here.)

Taking that trip was a threshold-crossing, and I wasn’t the same when I returned. I’m sure you have moments like this too, where you mark your life before and after the experience that served as a catalyst for transformation.

What I find fascinating about telling these stories is the way they change, even as they stay the same.

There’s the story I wrote in my travel journal as it unfolded. Then, the story I told my girlfriends immediately after I returned home. I shaped the story even further when I sat down to write the essay, Unwinding the Way, originally published in The Porch Magazine. And it changes each time I perform it for a different audience, contracting or widening circles of intimacy.

Vulnerability is always a consideration when creating connection, and even when I’m writing for or speaking to an audience of strangers, I’m asking myself, “how vulnerable can I be?” Or, “did I write something that scared me a little to say?” I think this is where the juice is, the sweetness that creates emotional resonance.

On the flip side, as much as I love witnessing the sometimes twinge-worthy horror of confessionalism run amok, you probably want to avoid airing it all on paper, on social media, or on the stage…you already know this. Enough said.

Facts are another consideration when crafting personal, true stories and can provide an important sense of grounding, both for yourself and the people engaging your story. What can be verified? What are things that might be hazy in your memory but are possible to be researched? Facts lend density and weight to the truth. When I began crafting Unwinding the Way for publication a few years after the retreat, there were all kinds of things I wanted to verify—Belfast landmarks, the political landscape the year I traveled, names of public spaces—just to offer a fuller glimpse of the world as it was outside the confines of what I could or couldn’t remember.

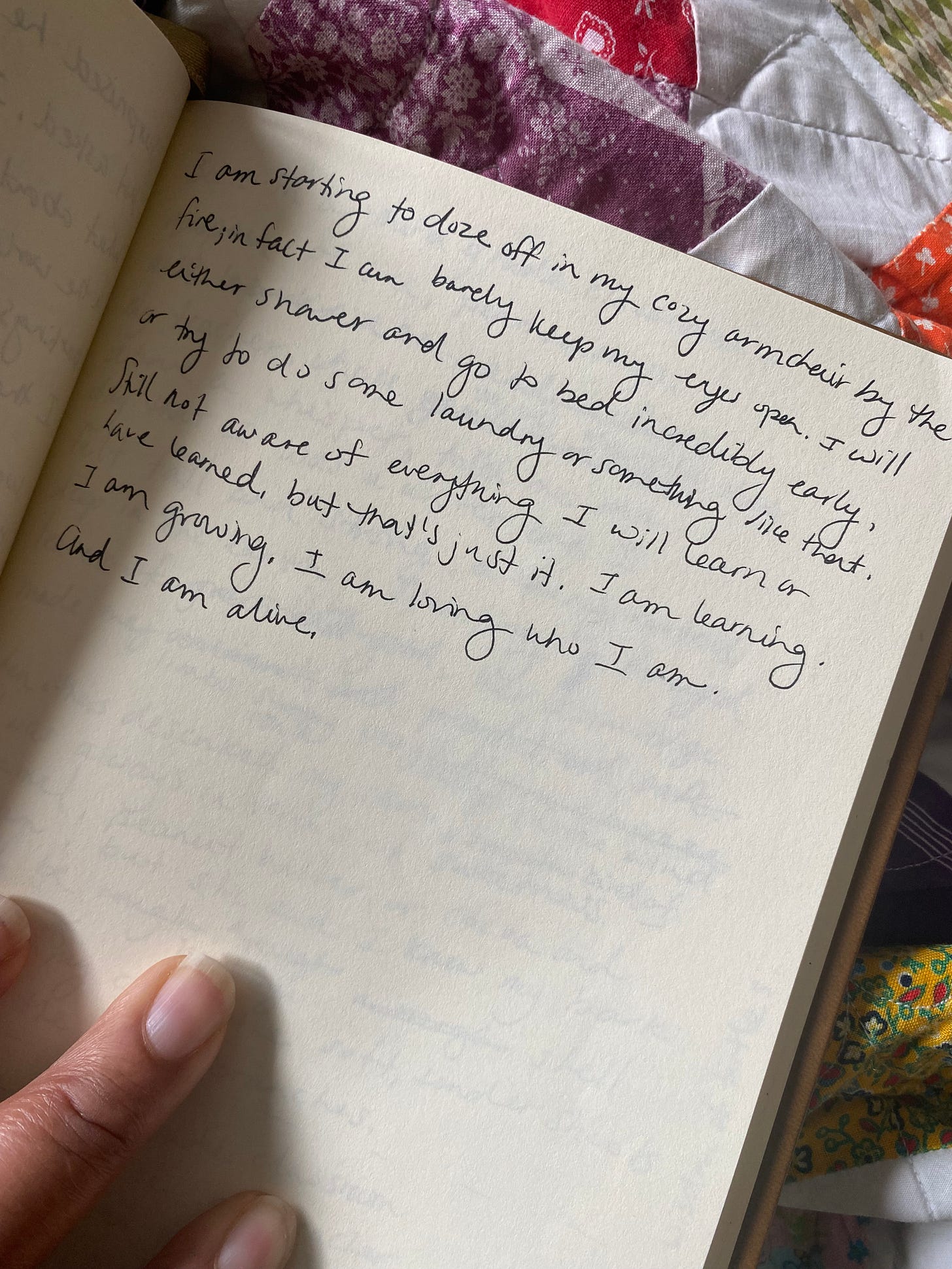

“I am learning. I am growing. I am loving who I am. And I am alive.”

This is what I wrote in my journal, and this is the simple, core truth of my Ireland retreat* story, no matter which ideas are emphasized, which details are revealed or held close to my heart. It’s a story I share because the truth is worth taking time with and then setting it free to dance between us.

Yours in telling stories,

*Maybe you can take a retreat to Northern Ireland, too?

Unwinding the Way

Audio experience here

Belfast unwound me. Slowly, suddenly, I found myself stretched as open and wide as the blue, unspooled ribbon of horizon across the Belfast Lough.

I knew the city had suffered.

From a childhood spent on America’s east coast, I sometimes heard reports blast from Northern Ireland, and interpreted those stories through the lens of a child’s eye. Men killed people with guns and bombs. It seemed as if the whole country exploded, spraying glass and wood and brick into a gray, unyielding sky. There was something called the IRA, and they were angry about things I didn’t understand. I was frightened. I couldn’t imagine how the people living in that far away place must have felt.

Now as an adult, from the moment I stepped off the bus that had brought me from Dublin to the Great Northern Mall in the heart of Belfast, I recognized the weight of a not too distant past, mingled with the quiet beauty of a place dedicated to its own transformation. I knew this retreat would be a gift.

Rumpled and groggy from travel, sitting in Caffè Nero with a freshly made cappuccino, I drew the first of many deep breaths. My book, Queen of the Fall, lay open on the table.

“So great are some hungers, so unrelenting,” Livingston writes, “that whatever even halfway fills them must be tried…What can we do but feed, then feed again, the tender shoots within us?”

The foundation of one of my core relationships had recently cracked, the betrayal a shock. My inner critic whispered, you should’ve known, like a mantra, as if knowing could’ve somehow shielded me from the pain of it. My heart was hungry for solidity, for peace, and a salve for its wounds. Looking out beyond my own life and into my community back home, I longed to bring the same salve to others. Through my work, I spent time with people living on the margins of society. They lived outside in tents, even when the ground sparkled with crystals of ice. They met, or dodged, their burnt-out, underpaid, social workers. They were well acquainted with others looking past them, in the same way you might look past a road sign or a fire hydrant. In May of 2016, it was a pre-Trump, pre-Brexit world, but America and all of her injustices still seemed able to compress the air in my lungs. Perhaps paradoxically, knowing some of what Belfast had suffered allowed me a certain sense of respite that no sandy beach vacation ever could.

This was a place where I could learn something about peace.

Watching a distinctly Northern Irish world flow past from the caffé’s large windows, I got lost in a kind of waking dream. Down the street, the Crown Bar presided over the corner like a gentleman full of secrets. Its architecture caught my untrained eye, and the cream-colored, upper half of the building appeared vaguely Victorian, though with warm dashes of sensual color I imagined Victorians might not have approved of. Across from the Crown, a film crew hovered around a large group of women, costumed in white leotards with red sashes. The women shivered like poppies in a spring freeze. I didn’t know it in that moment, but Samson and Goliath, the dual shipbuilding cranes used to create the Titanic stood sentry nearby, emblematic and bold. By the time my ride walked through the caffé door to take me to our lodging, I’d fallen in love.

What is love if not a moment of recognition we continue to return to again, and again, and again? Looking out into the world, our hearts connect us to a place. Either the landscape mirrors something within our own souls, or the story of a place, almost like a living entity, reaches out and takes us by the hand. Or sometimes we’re connected to another person, because in them we recognize a home. We know we can belong. In love, we’re continually recognizing and returning to the divine.

A few days before I was scheduled to fly into Dublin, I overheard my boss remark to a co-worker, “Jasmin will be out of the office…she’s going on a pilgrimage to Northern Ireland.” I watched my colleague’s eyes widen with admiration, and perhaps a touch of envy.

I wanted to shrug off the notion of a pilgrimage. It seemed to imply a mantle of spiritual loftiness I didn’t want to wear. I wasn’t a pilgrim, nor had I thought of this as a sacred journey.

But I was wrong.

Over the course of the week, I listened in suspense and awe to some of the politicians and clergy who had helped bring peace to their communities, in a time when neighborhoods were divided into deadly lines between Catholic and Protestant. Our group spoke of the U.S. civil rights movement, reminded that a movement is made up of thousands of individuals dedicated to the daily, sometimes mundane, work of dismantling oppression. We basked in music and poetry, and light pouring through the stained glass of beautiful, airy cathedrals.

In the quieter moments, healing had its way with me. Walking in the granite Mourne Mountains with a fellow traveler, we began to learn each other’s histories. It was an easy kinship between two people with brownish skin when everyone surrounding them was white—a recognition of the tender edges of our uniquely American grief.

I healed over sticky toffee and beer in a pub with a new friend, a local woman whose work paralleled my own caregiving back home.

Riding the train with my roommate, she and I bonded over our mutual penchant for solitude, discovering how easy it was to relax in each other’s company.

In our cottage, I healed in an armchair with my housemates, women with wonder and depth and courage in their souls. We drank tea, and diets-be-damned, we indulged in thick slices of bread slathered with butter. And one afternoon spent in silence, I wept beside a creek until I was spent, while grazing sheep kept benevolent watch over me. The creek rushed and tripped over its’ stones, absorbing my grief and eventually, washed it away.

In this way, I left a piece of myself in that Irish countryside, and the kelly green hills forgave me the intrusion.

On another day, after I’d taken some free time to wander through Belfast on my own, I stumbled across the Sunflower Pub. The bartender gave me a hearty welcome—any American who didn’t ask for Guinness, but a locally crafted stout, earned his respect. A live band had begun to strum a few songs and then it was time for me leave to catch the train back to our retreat lodging. Filled by music and the easygoing charm of the pub (and let’s be honest, I was a little tipsy), I hopped on the train, on the line I thought would take me back to where I needed to be.

Soon, as the train clipped further and further away from the city, I realized I didn’t recognize any of the stops. Commuters leaving work and going back home gradually emptied the train car. Looking out the window, wide swaths of heather blanketed the fields. We’d reached the end of the line, and I was one of the few passengers left to exit the train and step off onto the platform.

Inside the train station, a man with deep laugh lines around his eyes and eyebrows like bushy, white caterpillars stood at the ticket counter. As I approached, he took one look at me and asked kindly, “What’re ya’ doing all the way out here, love?”

Losing my way, I wanted to say. But, I’m making a new one.

Currently…

Reading: (or re-reading rather, for the of studying some fiction) Homegoing, by Yaa Gyasi

Cooking: It’s not cooking really, but I am enjoying a dash of allspice in my morning coffee. (Lovely reminder that fall and cooler temps will be here soon!)

Listening: “Love the Job: Finding the Labor We Love,” How to Survive the End of the World, a podcast by adrienne maree brown and Autumn Brown.